Better science hopes to save billions

Even under the most modest global warming scenarios, extreme El Niño years will occur twice as often – a new report from the University of New South Wales says.

Even under the most modest global warming scenarios, extreme El Niño years will occur twice as often – a new report from the University of New South Wales says.

A collaborative study, published in the journal Nature has for the first time revealed the cause of the unusually extreme weather events. The result of wild variations in the weather standards can be anything from floods to fire, each costing lives and livelihoods when they hit.

Research was led by a team from the UNSW Climate Change Research Centre and ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science.

The study has predicted that the bizarre weather events which led to extraordinary super-El Niño years in 1982 and 1997 are only set to increase, and the likely cause appears to be related to weakened ocean currents.

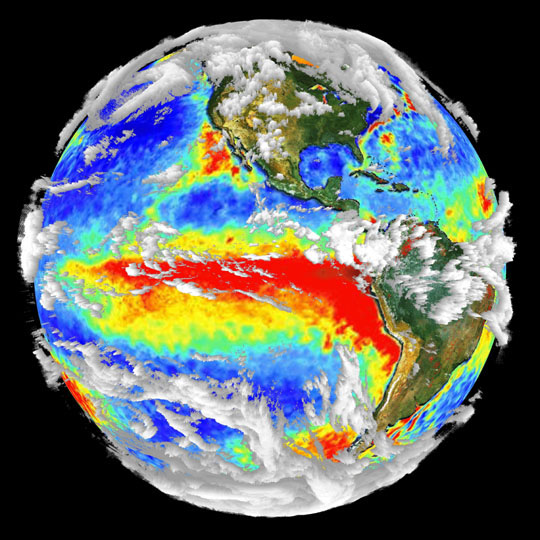

The unusual cases of El Niño events differ from the standard in that sea surface temperatures start warming in the west of the Pacific Basin and spread eastwards.

In normal El Niño conditions, ocean surface temperatures first warm in the colder eastern Pacific and then expand west, in the direction of the Trade Winds and the ocean currents along the equator.

Using existing observations and climate models, researchers found the key to the exacerbated El Niños is the weakening of westward flowing currents along the Equator in the Pacific Ocean.

The UNSW study says as these currents weakened and even reversed, it allowed the heat during unusual El Niños to spread more easily into the eastern Pacific.

With new clarity on the cause of the unusually extreme weather events in the past, researchers are now looking for ways to assess and predict future events – hoping to be more able to deal with their often expensive consequences.

Hotter-than-normal El Niños in 1982 and 1997 led to highly abnormal weather worldwide, causing disruption in fisheries and agriculture, as well as costing billions of dollars and the lives of tens of thousands of people.

During the 1982 event, in the US alone, crop losses were estimated at $10-12 billion (around $24 to $26 billion in current terms).

“While more frequent eastward propagating El Niños will be a symptom of a warming planet, further research is underway to determine the impact of such events in a climate that is going to be significantly warmer than today,” says co-author, Dr Wenju Cai, a senior scientist at CSIRO.

Print

Print